Nicholas A. Knouf

Assistant Professor, Cinema and Media Studies Program, Wellesley College

Art for Spooks, 2014, Nicholas A. Knouf and Claudia C. Pederson, hand bound case-bound book, iPad, found images and text, custom software. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The recent spying revelations that came from documents released by Edward Snowden have foregrounded the importance of Internet infrastructure to the surveillance apparatus. Infrastructure should be construed here in a socio-technical sense, both as the datacenters, routers, and fiber optic cables that constitute the physical plant of Internet traffic, as well as the human behaviors that interface with and make possible these material entities. Consider, for example, the ways in which the NSA has exploited Google’s failure to encrypt our data as it was sent between its datacenters, or how the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) has developed psychological operations to track behavior on social media sites in order to master the so-called “human terrain.” [1] As such, it behooves us as educators and artists to open up the black boxes of these dark programs, not only to “shed light” on obscured practices, but also to understand where the anxiety of surveillance is as detrimental as the surveillance itself. Given the shadowy world of state-sponsored surveillance, we have little to go on, and often must extrapolate from limited examples.

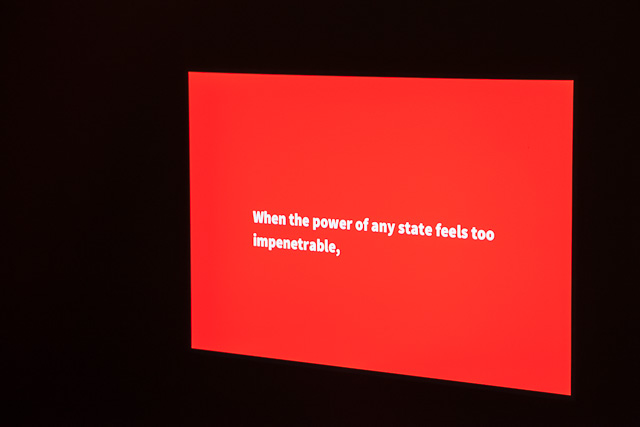

sylloge of codes, 2014, Nicholas A. Knouf, Raspberry Pi, pico projector, plywood, custom software. CC BY-SA 2.0.

sylloge of codes, 2014, Nicholas A. Knouf, Raspberry Pi, pico projector, plywood, custom software. CC BY-SA 2.0.

My two recent projects engage with these issues, but via different vectors. The first, sylloge of codes, is a series of site-specific invitations to think through new forms of communication in an age in which we are all-too-aware of mass surveillance. (The term “sylloge” refers to an ancient practice of collecting Greek and Roman inscriptions.) Our concerns over surveillance—couched within the language of big data and “Big Brother”—often blinds us from a simple fact: computers can only “understand” what they are programmed to “understand.” And since computers are very poor at understanding anything poetic, anything that does not fit into the logic of easily digestible signs, what if we began to communicate in different signs that could not be understood by computers? This is a very open question, and as such, sylloge of codes proposes that we begin to collect these potential new means of communication. The piece itself consists of a computer and projector hidden inside a box. The computer opens up a local wireless network, and visitors connect to this network and contribute their own ideas about new forms of communication, with the projector displaying prior contributions. The box becomes a sylloge for the 21st century, a collection of possibilities of resistance. sylloge of codes is currently being exhibited in Chile and the US and is designed to be easily transportable to new locations, with the translation localized for each particular site. By interacting with the piece, by engaging with the idea of communication-as-poetry, I hope to suggest a reactivation of language beyond a purely instrumental basis.

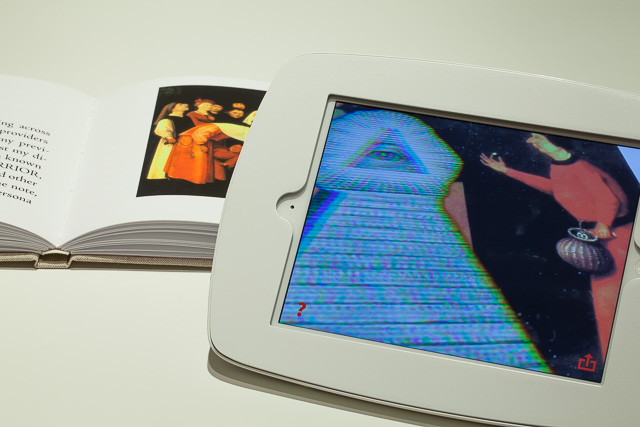

Art for Spooks, 2014, Nicholas A. Knouf and Claudia C. Pederson, hand bound case-bound book, iPad, found images and text, custom software. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The second piece, Art for Spooks, (produced with collaborator Claudia Pederson) examines the cultural imaginary of the NSA and GCHQ revelations, focusing in particular on the imagery used in the released documents. These images are at once perplexing and naïve, raising the question of exactly what kind of world these agents imagine we live in. The piece takes the form of a physical book and augmented reality tablet application that interfaces with the book, activating and twisting the collected images.

The text in the book is drawn from a number of sources, including “Ask Zelda” (an internal NSA advice columnist modeled after “Dear Abby”), an internal NSA blog post entitled “i hunt sysadmins,” and an internal GCHQ wiki page on current electronic surveillance capabilities. This text is then fed into a Markov model that is used to generate a series of imagined letters to and responses from “Zelda.” We selected images from the plethora of documents released by Snowden that were especially arresting, focusing on those that gave us some insight into the cultural imaginary of the NSA/GCHQ agents who produced these presentations. We then created augmentations of these images that commented upon this imaginary. Our use of the Markov model, the placement of images in conjunction with the text, and the selection of the augmentations themselves was all guided by Salvador Dalí’s “paranoiac-critical” method. [2] For Dalí, “Paranoiac-Critical Activity organizes and objectifies in an exclusivist manner the unlimited and unknown possibilities of systematic associations of subjective and objective phenomena appearing to us as irrational solicitations, solely by means of the obsessive idea.” [3] Contra the belief that today’s surveillance is best modeled by Foucault’s elaboration of Bentham’s panopticon, or Deleuze’s postulation of the societies of control, we rather focus on the processes of surveillance, the means by which models of surveillance come to be. Acknowledging Dalí’s own association with fascism, we nevertheless believe that it is paranoia that describes the workings of contemporary surveillance. For what is big data other than the creation of “systematic associations of subjective and objective phenomena?” And what is more paranoiac than arguing that we must “collect it all” simply to provide for the potential disruption of an “attack?”

Nevertheless, we have also created the project for the agents of the NSA/GCHQ themselves. In a certain way, the project is ironic. We imagine a bored office employee. We don’t know how she looks or what forms her daily activity. We only know that this person has access to a vast amount of data, data provided to her by programs approved by people much higher in the chain of command. Yet the public only sees people like Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning. What we are left with are PowerPoint presentations and other documents released by Snowden and other leakers, documents that are our only insight into the cultural imaginary of the surveillance agencies. The project was thus pieced together from those materials. This situation is complicated for two reasons. One the one hand, we know that there are people actively trying to do harm to those in the U.S. (as well as other nations), and thus a complete lack of surveillance will place the public in great danger. On the other hand, the rank-and-file employee uses systems designed and given legal justification by others with far more authority than she has, placing her into a vast bureaucracy with little ability to affect change. Our project is predicated on this nuance, an attempt to highlight the absurdity of the situation through the sympathetic positioning of the gallery visitor. We know that not everyone can become a whistleblower like Snowden or Manning. However, for those who do design these surveillance systems, we ask what might be done to imbue a different sort of ethics into their training.

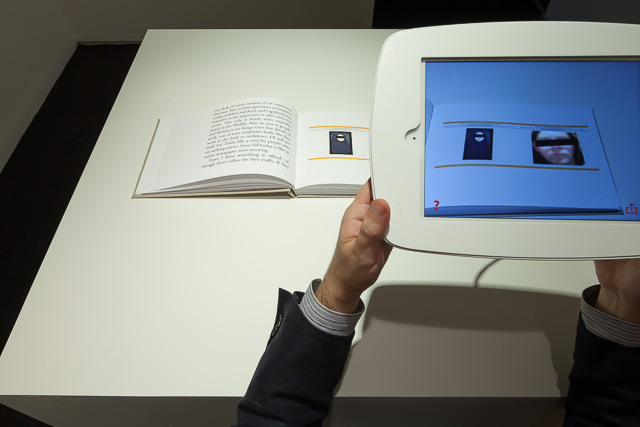

Art for Spooks, 2014, Nicholas A. Knouf and Claudia C. Pederson, handbound case-bound book, iPad, found images and text, custom software. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The project was also created to add more “disinformation” and point out the brittleness of surveillance. As people interact with the book, they can upload images to various social networking services. The metadata in those images is mangled so as to alter the GPS coordinates of the image (replacing them with locations of U.S. drone strikes in Pakistan), as well as to embed scholarly texts about surveillance in the various metadata text fields. If the visitor so chooses, she can upload the image to these social media services. We know that the NSA/GCHQ monitors and mines the metadata of images and other media on these services. So this mangling serves a double purpose: to highlight the brittleness of the system, as well as to provide the titular “art for spooks.”

Art for Spooks, 2014, Nicholas A. Knouf and Claudia C. Pederson, hand bound case-bound book, iPad, found images and text, custom software. CC BY-SA 2.0.

The images that are found in Art for Spooks highlight the abstractness of surveillance. All we have are data, data without any necessary indexical relationship to reality, without any necessary connection to the actual bodies found in these images. One image shows a man with his face obscured, holding a gun in one hand and a cell phone in the other, all underneath the title “Afghan – in the Mountains.” We do not know who this is; we do not know if this man is dead or alive. “He” is only an abstract image in a slide deck. Yet these “real abstractions” have severe effects in reality, where the (no)body in the image gets linked to a real body in the world, transforming that body into a target. We know, in the case of drone strikes, that these links have all-too-often been tenuous at best, and non-existent at worst. What happens when these abstractions are linked not to the body of the Other over there, but rather to your own body here?

References

- See Barton Gellman and Ashkan Soltani, “NSA infiltrates links to Yahoo, Google data centers worldwide, Snowden documents say,” October 30, 2013, accessed September 19, 2014, http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-_security/nsa-_infiltrates-_links-_to-_yahoo-_google-_data-_centers-_worldwide-_snowden-_documents-_say/2013/10/30/e51d661e-_4166-_11e3-_8b74-_d89d714ca4dd_story.html; and Richard Esposito, Matthew Cole, Mark Schone, and Glenn Greenwald, “Snowden docs reveal British spies snooped on YouTube and Facebook,” January 27, 2014, accessed September 19, 2014, http://investigations.nbcnews.com/_news/2014/01/27/22469304-_snowden-_docs-_reveal-_british-_spies-_snooped-_on-_youtube-_and-_facebook.

- Salvador Dalí, “The Conquest of the Irrational,” in The Collected Writings of Salvador Dalí, ed. and trans. Haim Finkelstein (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998 [1935]), 262–272.

- Ibid., 268.

Bio

Nicholas Knouf is an Assistant Professor of Cinema and Media Studies at Wellesley College. His scholarly and practice-based research explores the interstitial spaces between media studies, critical theory, digital art, and science and technology studies. He is currently working on a book project that explores the intertwined relationship between the sonic and informatic aspects of noise. His writings and projects have been published and presented internationally.